Also, there is a secondary heating effect from an open fireplace, that is from the masonry or stone it is constructed of. The masonry/stone heats up from the fire, especially if a fire is maintained for a length of time, its mass then convects to surrounding air and radiates energy, albeit the masonry/stone only holds residual heat and is not a heat generator, so the intensity is minimal compared to a fire. If the masonry/stone is of significant mass, a fire kept all day may cause the fireplace to continue to give off residual heat for hours after the fire has died. This is an efficiency if the fireplace is used to heat with, and it is located at least partially within the structure's building envelope. -- Hearths and chimneys with a lot of mass do well at capturing and then releasing residual heat. At an earlier time in England a fireplace interior to the structure of a house was considered an advancement against winter cold; a model of an old Suffolk farmhouse with a solid mass hearth and chimney is shown on the episode "The Secret Life of the Central Heating System" with host Tim Hunkin. YouTube has a post of it here, watch 23:43 through 25:05.

What then is the most efficient type of open fireplace? It is when the hearth, whether it be metal, masonry or stone, is situated within the living space so that all sides can convect and radiate its residual heat.

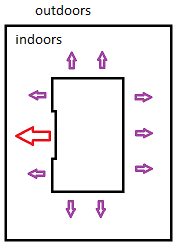

Depicted here is a masonry fireplace located entirely inside the perimeter of the structure. The red arrow represents the radiant heat given off by a fire in the open fireplace. The purple arrows represent the masonry giving off its residual heat in the form of convection and infrared radiation. Objects give off infrared radiation in all directions, but it is most intense perpendicular to the exposed face. In this illustration the residual heat is transferred to the interior space on all sides of the fireplace/chimney. The above example photo from a 1959 house shows the chimney/hearth inside the living space, the firewood burning open fireplace has a sort of decorative hood, clearly not enclosed at the top as smoke streaks dirty the brick face at its top. The below example is of a 1900 house, an interior and exterior view.

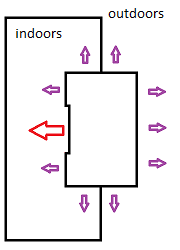

For this 1929 house, three sides of the fireplace and chimney are interior, though when the masonry is heated by a fire the outside exposed face is likely to convect more heat than the interior sides due to the difference of outside winter temperatures. The fireplace and chimney are on a gable end of the house. The main floor fireplace and mostly interior chimney should due well at maintaining draft.

This 1960 home has a masonry modified open fireplace which has three sides interior. However, the exterior siding covers over the exterior masonry, so that 2x4 wall framing may be insulating the exposed side of the lower part of the chimney.

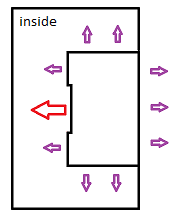

With a fireplace and chimney constructed midway into an exterior wall, if during the cold months the interior space is not heated then the residual heat will transferred evenly between the inside and outside, but if inside is conditioned (such as by a furnace) the difference in outside temperatures will cause the exterior masonry of the chimney to convect a greater share of its residual heat to the outside. The two example photos are of a fireplace/chimney on a 1925 house that sits midway in the exterior wall.

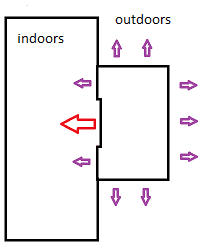

In this illustration most of the residual heat is transferred to the outside, regardless of the temperature difference between inside and outside. The example photos are of a house built in 1986, note the structure of the chimney is flush with the interior wall and the decorative brick face sits inside the building envelope. It was common in the 1940s for fireplace openings to be flush with the interior wall.