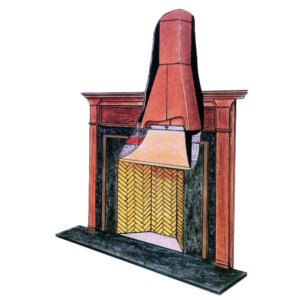

Late AD 18th century, Benjamin Thompson (aka Count Rumford) proposed a new fireplace that became known as the Rumford fireplace. Until Thompson's research on heat, fireplaces often failed to capture all of the smoke from the fire. One of the features of a Rumford fireplace were the angled side walls that reflected more radiant heat from the fire into the room. The additional reflected radiant heat of a Rumford fireplace enabled a Rumford fireplace to be constructed smaller than a typical box shaped fireplace in order to produce the same amount of felt radiant heat from the fire. As a result, many existing fireplaces used strictly for heating were able to be converted into Rumford fireplaces. Fireplaces shaped like a box usually have firewood laid horizontally; new Rumsford fireplaces tend to be tall so that leaning firewood vertically against the back of a Rumsford fireplace is typical; converted fireplaces may still remain wide so that short lengths of firewood are laid horizontally. Another feature of a Rumford fireplace was the increased draft at the chimney flue throat which captured the smoke from the fire. Whether a Rumford fireplace succeeded at capturing all of the smoke depended on the understanding of the Rumford principles by the installer. The increased draft was generated as a result of the chimney flue throat being restricted (smaller cross section) in contrast to the cross section of the flue above, and by the pargeting of the flue throat to reduce turburlence as the exhaust passed up and into the flue. Chimneys at the time (18th century) and into much of the 19th century were unlined with the exposed brick and mortar causing resistance in the form of turbulence of the exhaust.

The Rumford fireplace was and still is superior to a typical box shaped fireplace when used as an open fireplace. Construction of typical box shaped heating fireplaces continued; sometime in the 19th century ratios between the sizes of the firebox, flue cross section, and chimney height were recognized for generating appropriate draft strengths; too weak a draft and smoke spills into the living space, too strong a draft causes the fuel to burn too fast and hot, so that the advantage of a Rumford fireplace expelling most or all of the smoke was then met by the typical box shaped fireplace design when served by an appropriately sized chimney and flue cross section; though a Rumford fireplace still has the advantage over a typical box shaped fireplace in that it reflects more of the fire's radiant heat into the room.

Superior Clay has excellent images that illustrate a Rumford fireplace ( here ). Also, Buckley Rumford Company has lots of information about Rumford fireplaces, here. These companies offer clay tiles so that a chimney can be constructed as more of a kit, which speeds construction and is already sized with the appropriate ratios for optimal performance, and also enables masons with minimal understanding of Rumford fireplaces to be successful.

The use of the fireplace is a very old method of house heating. As ordinarily constructed fireplaces are not efficient and economical. The only warming effect is produced by the heat given off by radiation from the back, sides, and hearth of the fireplace. Practically no heating effect is produced by convection ; that is, by air currents. The air passes through the fire, is heated, and passes up the chimney, carrying with it the heat required to raise its temperature from that at which it entered the room and at the same time drawing into the room outside air of a lower temperature. The effect of the cold air thus brought into the room is particularly noticeable in parts of the room farthest from the fire. -- from the USDA Farmer's Bulletin No. 1230, CHIMNEYS & FIREPLACES, December 1921

The open fireplace, however, has its place as an auxiliary to the heating plant and for the hominess that a burning fire imparts to the room. -- from the USDA Farmer's Bulletin No. 1230, CHIMNEYS & FIREPLACES, December 1921

A point that is of interest here is that in order to get more heat from an open fire, the assumption is to feed the fire more fuel to have a larger blaze, and the result is more radiant heat. However, more convective heat warms more room air that escapes up the chimney which draws in equally more air into the living space from the outside. There may be an increase in radiant heat felt from the fire, but there is no noticeable lasting heat gain to the living space, because the increased makeup air from the outside chills any accumulation of radiant heat from objects in the room.

Any one who has depended upon a fireplace to heat a room knows that the part of the room farthest from the fire is the coldest and that the temperature around the windows is especially low. In fact the harder the fire burns the colder it is at the windows. -- from the USDA Farmer's Bulletin No. 1230, CHIMNEYS & FIREPLACES, December 1921

The principal warming effect of a fireplace is produced by the radiant heat from the fire and from the hot back, sides, and hearth. In the ordinary fireplace practically no heating effect is produced by convection, that is, by air current. Air passes through the fire and up the chimney, carrying with it the heat absorbed from the fire; at the same time outside air of a lower temperature is drawn into the room. The effect of the cold air thus brought into the room is particularly noticeable farthest from the fire. Heat radiation, like light, travels in straight lines, and unless one is within range of such radiation, little heat is felt. -- from the USDA Farmers' Bulletin No. 1889, FIREPLACES & CHIMNEYS, December 1941

In homes where chimneys had been installed during the wood-burning era, the desire for more heating may have been a spur to switch to coal. A fireplace was fixed in size by the brick- or stonework and its chimney. A roaring blaze could be expanded only up to a point. There was a very real limit to the amount of fuel you could add to your fire. If you wanted more heat to compensate for the 70 per cent that was escaping straight up the chimney, you needed to burn something that produced a hotter flame. Coal delivered more heat. -- from The Domestic Revolution by Ruth Goodman, which is about England, chapter 3, in the section 'First movers (and furnishers)'

There is no requirement to construct an open fireplace according to established or recommended dimensions, but there are practical considerations that have caused open fireplaces to be constructed of a typical shape for firewood, coal, and gas burning appliances. Those considerations are of the capture of the smoke/exhaust the fuel generates, the loading and maintenance of the fuel, and its performance. Common deviations from typical construction are those fireplaces with an arched opening, a double sided fireplace, and three sided fireplaces (three sides that are open).

-- insert example of an arched fireplace --

-- insert example of a double sided fireplace --

-- insert example of a three sided fireplace --

Where cordwood (4 feet long) is cut in half, a 30-inch width is desirable for a fireplace [constructed to burn wood]; but, where coal is burned, the opening can be narrower. Thirty inches is a practical height for the convenient tending of a fire where the width is less than 6 feet; ... The higher the opening, the greater the chance of a smoky fireplace. -- from the USDA Farmers' Bulletin No. 1889, FIREPLACES & CHIMNEYS, December 1941

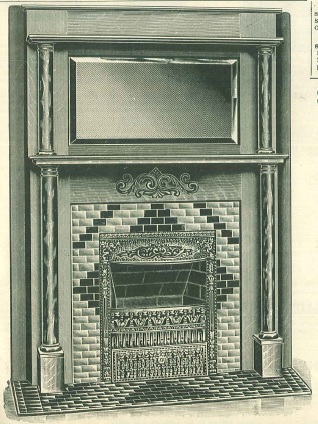

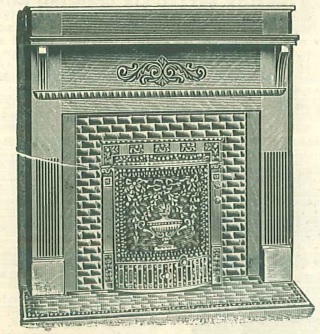

Ordinary (non-Rumford) firewood burning fireplaces tend to be wider than their height, in part because firewood pieces are stacked horizontally along their length and begin to collapse when they burn down. Coal is a more dense pack of fuel than firewood, requiring less space than firewood, also coal easily piles up... in North America, coal baskets were often purchased to set in the hearth for the coal to burn in, people that switched to burn coal in open fireplaces often bricked in the sides of the fireplace to limit the area that room air could rush into the fire, where the bricks were set in close to the sides of the coal baskets, resulting in a fireplace that is taller than it is wide. Many coal baskets had cast in firebacks or were flared on the sides. Coal baskets with flared sides were used in fireboxes that were bricked in so the sides were angled like a Rumsford fireplace. Baskets were offered in different sizes and stylings.

'Hard' coals require combustion air to flow from underneath, and as it burns the ash fills the voids between the coal pieces in the pile which chokes off the paths the combustion air can take from underneath. Tending to a hard coal fire is an effort to clear the ash from the coal pile, shaking is the preferred method. Metal rods were used as pokers early on, but later baskets were developed with a movable grate to make shaking easier. A coal basket provides space below the pile for the ash to fall through to and also makes cleaning ash from the firebox easy while the fire is still burning. Many grades of 'soft' coal do not require baskets, but baskets were still used because of the ease of clearing ash from the firebox while the fire burned.

Both of these photos are of fireplaces constructed for burning coal which is obvious from their height to width ratio. The photo to the left concerns a renovated 1870 house, and what is evidently a coal burning fireplace that has had its coal basket and cover, or cast iron fireplace taken out and a firewood grate put in with firewood. The photo to the right concerns a 1905 house, where smoke rollout has dirtied the fireplace face above the decorative cover, mostly likely it is wood smoke; note that the smoke trail suggests it floated up behind the cast iron front hood. In residential communities, coal burning open fireplaces would have burned 'hard' coal that produces little smoke, but depends on whether it is readily available. In rural houses with access to soft coal, coal burning open fireplaces would have burned 'soft' coal as it is less expensive but produces lots of smoke for about 20 to 30 minutes after each refueling.

Manufacturers eventually began to sell decorative cast iron 'fireplaces' with stylish fronts and covers like the examples above and below (iron covers pictured below); some were just used as covers over the face of the firebox (the first photo above shows a free standing coal basket in the fireplace with a separate surround across the fireplace opening); others were functionally iron fireplaces that set inside a masonry chimney (such as the above second and third photos). The second photo above is an example with its integrated coal basket supported by the sides of the iron insert. There were also brass decorative fronts and covers that were sold, though I am still unclear if those were marketed to a particular setup, my impression is they were only decorated covers for coal fireplaces that had separate freestanding iron coal baskets.

From the late 19th century many masonry fireplaces were specifically constructed for burning coal and to receive these decorative cast iron 'fireplaces'; this continued into the 1920s. For most of these iron fireplaces (above) that have the flush front all the parts are static. The two photos of the green tiled fireplaces (above), though the mantels and tiling are nearly the same, these are from different homes. The fireplaces in the two left photos have had their hearths covered over by carpet.

Some manufacturer and models, included features like integrated shaker grates, and/or exhaust dampers with control arms that were operated from the front.

The 1904 Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog offers a number of coal fireplaces or coal fireplaces with mantel and accessories. Here are screenshots of two, one with a mirror above the mantel. Notice one depicts what the fireplace looks like with the summer front (cover) attached, sold as an accessory.

As manufactured gas began being marketed in North America in the 1880s, and later natural gas, gas fired faux logs and fireplace inserts were installed into existing fireplaces, these were either open flame or radiant heaters. Antique gas burning fireplace inserts often were constructed to look like an elevated grate with fake wood or coal piled on and were set into the fireplace rather than appearing as an appliance that covered over the face of the fireplace. There were gas burning fireplace inserts and faux logs that were wide and intended to be setup in a fireplace that was constructed for wood burning, and some that were narrow and intended to be setup in a fireplace that was constructed for coal burning. Probably in the 1920s, fireplaces were constructed specifically for gas burning units. Gas is a fuel that is delivered to the flame from below rather than being piled onto the fire like a solid fuel (wood or coal). Burning gas in a fireplace for heat does not change the functionality of a fireplace, so to maximize the radiant heat of a gas fire the burners which were much smaller than a pile of firewood or coal were usually arrayed low and horizontally across the width of the firebox often with only one row of orrifices along the burner. Therefore gas burning appliances, whether faux logs or faux coal piles or gas fireplace inserts, the firebox built specifically for those gas appliances would not require much depth. In practice the typical appliance design of the face of the gas burning units were of a square dimension. Therefore, when we see houses with fireplaces that are shallow depth it usually indicates it was built for a gas appliance, often these fireplaces have mostly square openings.

Antique gas burning appliances used open flames to heat with. Due to radiant heat being the warming effect of the fire, antique gas burning appliances quickly began being constructed with ceramic lattices and/or asbestos blankets that set directly over the flames in order to be heated and then radiate their residual heat into the room. Generally you should have a carbon monoxide detector (or two) near any fuel burning appliance in a house; this strategy is just as important with antique gas burning appliances, even when operated while set in an open fireplace.

This 1919 house has a fireplace that appears to have been constructed for this particular radiant gas burning unit. Often the grills on these units are just to screen the void of the open fireplace. I did not have the opportunity to look closely at this unit, but it could be that the lower and upper registers are intended to circulate room air against the back of the unit, a sort of modified fireplace feature (explained on the next page). At the bottom of the ceramic lattice is a removable metal cover, beneath it is the gas burner. Later antique gas burning appliances, this unit probably one of those, were constructed so that the flame was not exposed; think todlers, young children, and pets; of course this made the appliance more of a room heater than a "fire"place. Note the ratio of the unit is mostly square.